The 15th floor

Inside immigration court in Chicago, where expedited removal has now hit the “sanctuary city” thousands of miles away from the border.

by Steve Held May 27, 2025

Share this article:

Editorial note: out of an abundance of caution and concern for asylum seekers’ safety, we’ve chosen not to publish names of those detained by ICE in this story. If you are an attorney or family member trying to locate someone, please reach out.

In the latest escalation in the administration’s war on migrants, ICE agents have been dismissing cases, then arresting people at their immigration hearings in cities across the U.S. The Chicago Tribune and Chicago Sun-Times both reported on similar arrests here in Chicago on May 22. Attorneys and advocates, already stretched so very thin, are scrambling to update guidance for migrants who have been advised to never miss their court hearings. We are officially in uncharted territory.

I wanted to see for myself what was happening and who ICE was targeting, so I went to Chicago’s immigration court when they opened on Friday, May 23.

I arrived at 55 E. Monroe shortly after 8:00 am.

Like every government office, you have to pass through a security screening. On one side is a set of windows with clerks where people can file their paperwork. On the other side is a small waiting room.

In the waiting room, a panel of screens resembling airline departures rolls through a lengthy list of names, times, and assigned courtroom numbers. I asked security if I could attend hearings in any room. They said I could attend any “master hearing.”

I was not very familiar with the details of this part of the immigration and asylum process, so I expected to see some cases designated as master hearings—but there were none. Next to the screens were paper copies of lists also showing times, names, and courtrooms, but they didn’t match the screens. These also had nothing designated as a master hearing; they were all removal cases.

Adding to the confusion, each courtroom also had a schedule taped up outside the courtroom, which, you guessed it—matched neither of the other lists. After asking a security guard about the courtroom list, he ripped it off the wall and crumpled it up, saying it was yesterday’s.

I decided to try my luck with an attorney there who had been giving information to people arriving for their hearings. She said she’d been informed all the screens were wrong, and people should only look at the printed lists off to the side.

“This is so confusing,” I sighed.

“If you think it’s confusing, imagine how they feel,” she replied, nodding to the chaotic waiting room.

She had a point, and I had a little experience with how confusing immigration and every day life could be for a new arrival.

Through my wife’s volunteer work, I have gotten to know a group of Afghan men who were brought here when the U.S. abandoned Afghanistan. As men who had aided the U.S. military occupation in some way, they went through an expedited process to receive asylum, and eventually, a green card.

That expedited process was confusing, glacially slow, and opaque, so it’s not surprising to see that the normal process is worse on all counts.

It has also been, at times, a comedy of errors. Last summer, during a brutal heat wave, the men lost power (and consequently, air conditioning) in their shared apartment. It turned out that the aid organization we thought was taking care of their utility bills was not, and the bill had not been paid in over a year. Complicating our attempts to get ComEd to restore their power, the men had only lived in the unit for six months. It took several days, but we eventually got it restored.

The entire experience highlighted the heartlessness of the system to me. Several of the Afghan men have families—one has a son he’s never met—who remain at risk of violence from the Taliban, nearly four years after the evacuation. The family reunification process is incredibly difficult to navigate, with no help from the government. Yet somehow, despite all of this, the men believe in a version of America that would make our propagandists proud.

Back in the waiting room, mostly in small groups of two or three, I see a room full of people trying to navigate what should be a simple step, to attend a hearing. After a quick online search, I learned that a master calendar hearing is just an early step in the removal process. Basically, this is where a person is advised by the judge of the charges against them and they can admit or deny them.

An individual can have more than one master calendar hearing. In several cases I witnessed, people were at their second master calendar hearing after requesting time to get an attorney in their first.

It’s important to know that these hearings are not where a judge decides that someone should be removed. In a future hearing, the individual should get to present evidence where the immigration judge will decide whether they get relief or if a removal order will be entered.

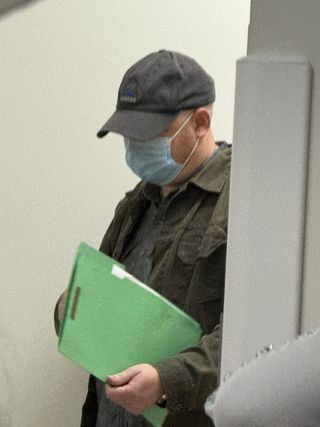

As I was sorting through this, I noticed a group of at least five men and one woman who stood out from the rest of the crowd, primarily because most of them appeared to be white. All were in casual plain clothes, most of the men and the woman wore baseball caps. None were masked—yet. At least one had a DHS badge on his belt. An attorney confirmed that these were all ICE agents.

The agents checked the schedule on the wall against papers they carried in colored folders.

An older man in a suit conferred with the group, asking for the specific names of people they were looking for. I later learned this was the DHS attorney in the proceedings.

The waiting room cleared out as people figured out where they should be, with most of the hearings slated for 9:00 am. The ICE agents were given a box of surgical masks by one of the security guards. Donning their masks to hide their faces, most of the ICE agents entered courtroom number three. Two lingered in the hallway for a while. Later, I would learn why.

Only one man and woman remained in the waiting room. They appeared to be making several anxious phone calls. From what I gathered, they had expected an attorney to meet them, but he wasn’t there. Eventually, they headed into courtroom three without counsel. At the time I didn’t connect the dots, but shortly after that, the ICE agents in the hallway were gone.

Inside the courtroom, Judge Brendan Curran was presiding. The entire team of ICE agents was seated in the back row by the door.

The first case I witnessed involved a man from Venezuela. His first master calendar hearing was last summer. He said he had entered the country to appear at a scheduled appointment at the border to apply for asylum, and then remained. Despite that, the government argued that he didn’t have a visa, so he still entered the country illegally. Curran concurred.

After a few more questions, Curran advised the man to get an attorney, and scheduled another hearing to weigh the merits of his asylum case in July 2026.

The next few cases proceeded along similar lines.

Then the judge called the case for a man from Jordan, dialing in an Arabic interpreter. This was the man who lingered in the lobby, waiting for an attorney who never arrived. He appeared to be about the same age as our Afghan friends. I couldn’t stop thinking about them as the hearing continued.

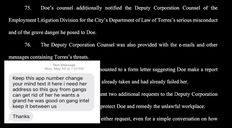

Based on the looks exchanged between the lead ICE agent and the DHS attorney as he was called, it was clear this was not going to go like the earlier cases.

As in the earlier cases, the man had previously appeared before a judge last summer. With no attorney present, the judge said he had planned to reset the case for a date in January to allow more time for him to retain counsel.

DHS had other plans, however. They motioned to dismiss the case.

The judge informed the man that he had ten days to respond to the government’s motion to dismiss. Then, seeing the ICE agents standing in the back, the judge added that while he still had ten days to respond, it was possible that ICE would take him into custody immediately—which of course is what happened.

I followed him and the woman who was with him, who he described as his uncle’s wife, out into the hallway. Volunteers with the National Immigration Justice Center and DePaul tried to quickly counsel his aunt, who was fluent in English, on what was about to happen and resources that she could use to try to find help.

After a few minutes, the ICE agents swiftly moved in, and informed him he was being detained. It was clear that it had not occurred to him or his aunt that he might be snatched by federal agents today—after all, he was following the rules, and had attended his hearing as required. His aunt was visibly shaken and upset.

Agents took the man down a long hallway to a set of internal elevators. I rushed down to the lobby and the parking garage, but I never saw where they went.

When I returned to the 15th floor, it wasn’t long before the ICE agents returned for their next target. This time, I loitered in the hallway, so I did not hear the specifics of the case. Soon after, a lone man exited the courtroom where agents were waiting. Unlike most people that day, he did not appear to have a friend or family with him.

Agents closed in around him, looked through his papers, and disappeared down the same elevator.

About this story

Related Stories

-

Police accountability commission under fire: “You have state power—fucking use it.”

Chicagoans shared accounts of Chicago police helping ICE and Border Patrol agents at a public listening session they criticized as long overdue.

-

CPD leaders knew cop proposed hiring hitman to kill fellow detective, new federal lawsuit alleges

The lawsuit alleges an officer faced years of violent abuse and threats at the hands of another detective while top brass and city officials have refused to investigate or discipline him.

-

Identified: federal agents who pointed gun, punched detainee in Evanston

Unraveled has verified a hate speech-laden X account belonging to U.S. Border Patrol agent Timothy Donahue, who was seen in numerous viral videos during Operation Midway Blitz. He and another agent, Thomas Parsons, have now been identified via public records released by the City of Evanston.