Support Unraveled

Your support funds our investigative and on-the-ground reporting. Thank you for uplifting independent journalism!

SupportA vast network of new license plate cameras has exploded across Illinois in recent years—paid for by state grants to fight retail crime. With the federal government clamoring for more information on people’s movements, how worried should we be about leaving our privacy in the hands of Flock Safety?

by Steve Held and Raven Geary Aug 19, 2025

Share this article:

For six months, the world had been watching in horror as Israel annihilated the Gaza strip. In the millions, people had marched, rallied, blockaded roads, launched hunger strikes, and damaged weapons factories. A young man set himself on fire and livestreamed his own death. But it would be students at Columbia University, in the heart of New York City, who would open a new front.

Within days of Columbia students setting up a solidarity encampment on campus, schools across the country exploded in protest. Police cracked down at full tilt, beating and jailing thousands of keffiyeh-clad anti-war activists. Some occupied university lawns for weeks before finally facing violent predawn sweeps. Others were immediately met with SWAT teams, clouds of tear gas, and sheriff’s officers on horseback.

During the day, they rallied. At night, they—a generation witness to the horrors of war live, up close, and personal on a level seemingly designed to break a human’s brain, if not a soul—scrolled helplessly through high definition videos of people disemboweled by shrapnel and babies with exploded heads.

At the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign, protesters felt optimistic about their chances of camping out on the quad.

“We were firmly in the zone of, we didn’t think this would even have a legal response, because, really?” said Valentina K., a protester who asked we not use her last name. “Students put tents on campus all the time.”

She dropped off supplies and began setting up camp with others in opposition to the war.

University cops treated the action like an existential threat.

“There’s like 100 cops. Every police force in the county was there. There was a sense in the air of, are we gonna get shot? Is this like Kent State? Are they really gonna do this over students putting tents on campus?”

Following an attack by campus police, reinforced by neighboring departments, activists managed to rebuild. They remained there for two weeks until graduation.

But the worst for some was yet to come.

UIUC police scoured social media posts and surveillance footage for anything they could find to help them identify students. According to police reports, they extracted still photos of protesters’ faces from their body-worn camera videos. The photos were sent to the secretary of state’s office, where they used facial recognition technology to find matching drivers’ license photos.

In the end, it was one specific kind of surveillance equipment—an automated license plate reader, or an ALPR—that would be used to link video of Valentina at the encampment to the vehicle she drove there.

Police departments across the nation used surveillance tools to identify Black Lives Matter protesters in 2020. Five years later, the tentacles of state surveillance have unfurled even further.

The cameras have sparked legal and privacy concerns. 404 Media recently revealed a Texas deputy ran a national search of an ALPR database to look for a woman who allegedly self-administered an abortion. Audit logs obtained by anonymous researchers also show how police in and outside Illinois have used the network of one particular ALPR manufacturer, Flock Safety, to assist ICE with immigration investigations. Both of these scenarios are prohibited under Illinois law.

Illinois Secretary of State Alexi Giannoulias has called upon Attorney General Kwame Raoul to investigate these incidents. The AG has not yet publicly commented on the issue.

On its face, all of this dystopian tech wasn’t given to cops to track protesters, abortion seekers, or immigrants.

It was doled out, ostensibly, to battle something else entirely.

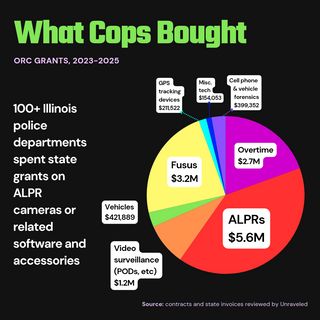

Since 2023, Raoul’s office has showered $15 million in state grants on police to fight organized retail crime. More than two-thirds of that money went toward new surveillance technology for cops: license plate readers, GPS launchers, hundreds of new video surveillance cameras, and tools to crack phones, computers, and vehicle infotainment systems.

Millions of this was spent with one primary ALPR vendor, which also happens to be the same one Giannoulias is promising to look into: Flock Safety.

Billing itself as “the first large-scale, public-private collaboration of its kind in Illinois,” the Organized Retail Crime Task Force is a conglomeration of law enforcement agencies and business interests, including big name retailers like Home Depot, Target, and Walgreens. It was created amid an industry-created retail crime panic the National Retail Federation would later admit was overstated.

Viral videos that emerged following the outbreak of COVID-19 contributed to endless media coverage of every level of retail crime from ordinary shoplifting to train car heists. Leaning on the police for store security has been a trend in retail; in 2023, Walmart announced they were building a police substation in one of their Atlanta stores. The irony is: while outsourcing more of their security needs to police, retailers have reduced staff and leaned heavily into self-checkout lanes, both of which have been shown to increase theft.

If the goal was drastically expanding state surveillance, by all means, the program has been a smashing success. ALPRs like the one used to identify Valentina are seemingly popping up everywhere—including 650 new cameras in Illinois cities since 2023, according to contracts and invoices from over 100 police departments reviewed by Unraveled. The true number is likely higher, but not all departments provided invoices.

By comparison, over a six-year span, the Illinois State Police installed 665 ALPR cameras under the Tamara Clayton Expressway Camera Act, a program created with the sole purpose of increasing surveillance on Illinois expressways.

As recently as February, Raoul lobbied Congress to establish a new Organized Retail Crime Coordination Center within the Department of Homeland Security. The proposed legislation would also increase criminal penalties and data sharing between states and federal agencies.

Raoul’s office did not respond to our multiple inquiries for this story.

Two companies dominate the automated license plate reader market: Flock Safety and Motorola Solutions. Both market their ALPRs to police, businesses, and home owner associations.

Flock’s national network includes more than 83,000 ALPRs. The company says it collects 20 billion license plate scans per month. The same metrics aren’t available for Motorola, though they claim to have a database with over 73.5 billion plate scans.

Invented by the British, the first license plate readers were deployed to track members of the Irish Republican Army in the 1990s before quickly making their way to the United States, where Customs & Border Patrol installed them to monitor border traffic. Municipal police departments began adopting the technology in the 2000s.

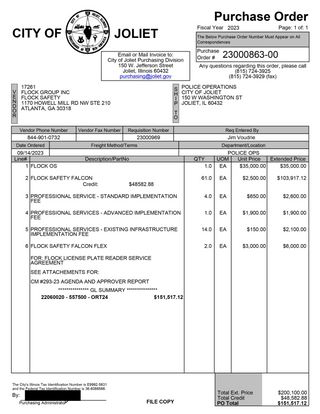

The inexpensive high-speed cameras capture and process images of passing vehicles. They are usually mounted on utility poles, but can also be attached to vehicles, trailers, or other temporary locations. Early uses focused on comparing license plates against a “hotlist” of vehicles police were looking for, such as those with unpaid tickets, or ones that had been stolen. The cost to install a typical fixed-ALPR camera is about $3,000.

Today’s networked, AI-enabled systems are much more intrusive. Police departments can now share their ALPR network with other agencies both in-state and out. A small number of departments publish so-called “transparency portals” that show who they share with, along with a few basic statistics.

ALPRs come paired with software packages from the vendors, such as FlockOS and Motorola’s Vigilant VehicleManager. These systems create “fingerprints” of vehicles, recording the license plate, make, model, and color of the vehicle—and any other unique characteristics, such as visible damage, a spoiler, or roof rack. They use AI to identify patterns, such as vehicles frequently spotted together, vehicles seen in multiple locations, or if a vehicle is exhibiting “suspicious” behavior.

Like other forms of surveillance, the ALPRs become more powerful when combined into larger networks. Police departments across the U.S. are investing heavily in real-time crime centers (RTCCs), expensive surveillance software platforms that integrate live video from police and businesses, license plate readers, gunshot detection systems, drones, body-worn cameras, police vehicles’ GPS, and other tech into a single view. FlockOS has evolved into an RTCC to compete with dedicated RTCC platforms like Axon’s Fusus.

As the technology has become cheaper, interconnected, and equipped with AI, the insights it can glean about individuals is expanding rapidly. With more than 100,000 ALPRs across the U.S. collecting tens of billions of plate scans per month, the net effect begins to resemble warrantless GPS tracking by an AI Big Brother. The Illinois State Police ALPR network alone captured over 2.2 billion vehicles—200 times the number of registered cars in the state—on interstates and tollways in 2024.

With more police departments buying their own vehicle-mounted ALPR units, even cars parked on streets or in public lots can be vacuumed into the system. If you travel by car anywhere but the most remote areas of the country, there is no question your movements are being tracked. Luigi Mangione’s choice to take a bus into New York City—followed immediately by a bicycle ride and a train ride after allegedly shooting UnitedHealth CEO Brian Thompson—is likely what enabled him to flee the state and confound police. Had he been in a personal vehicle, the manhunt would’ve been over quickly.

Many municipalities install ALPRs near busy destinations. Some even create a perimeter around their city to track every vehicle coming or going. Evanston’s ALPR locations, mapped by the Evanston RoundTable, illustrate the concept:

In Greers Ferry, Arkansas, the city installed an ALPR directly in front of a private residence, raising Fourth Amendment concerns as the camera took photos of their yard every time a car passed. The family was photographed every time they left or returned home. The not-for-profit law firm Institute for Justice persuaded local officials to relocate the camera.

Flock’s product roadmap continues to slash away at any concept of privacy. Their tagline for a new law enforcement product, Nova, is “Search once. See everything.”

As reported by 404 Media, Nova claims to combine license plate numbers with personal identifying information Flock has accumulated from social media and data aggregators. With only a license plate lookup, police can be served up information like the owner’s relatives, associates, employer, and police records.

“Powerful surveillance tools pose a significant threat to the civil liberties of all people,” Ed Yohnka of ACLU Illinois told us. “Surveillance cameras that utilize facial recognition technology, automated license plate readers and other tools allow government officials to track and snoop into each of our lives with no meaningful or articulable reason. Rather, these tools give the government a broad ability to gather information about where we go, who we visit and how we spend our time.”

Even smaller municipalities collect huge amounts of data. Transparency portals for police departments in Roselle, Champaign, and Oak Park each report recording approximately 400,000 vehicles in the past 30 days alone. But FOIA requests that would illuminate how police are using their license plate databases are routinely denied. Departments cite the state’s FOIA statute, which broadly exempts disclosure of “information gathered or records created from the use of automatic license plate readers.”

The statute as written was intended to protect people’s privacy.

Your support funds our investigative and on-the-ground reporting. Thank you for uplifting independent journalism!

Support

After forming the Organized Retail Crime Task Force, Raoul lobbied for the INFORM Consumers Act to define organized retail theft as a new crime, with harsher penalties alongside new powers for prosecutors.

Organized retail crime is defined—by the industry—as a criminal enterprise employing individuals to execute highly coordinated, large-scale thefts of retail merchandise to be sold through fencing operations. The bill defines organized retail theft so loosely that two people working together to shoplift and sell even a small amount of merchandise could be charged more severely.

Raoul partnered with Rob Kerr, president and CEO of the Illinois Retail Merchants Association, to champion the bill in an op-ed.

“Policy makers must address crime that is plaguing significant portions of our state and keeping residents away from downtown streets, neighborhood shopping districts and our city’s magnificent entertainment corridors,” they wrote.

Not everyone supported the bill. Chicago Appleseed, a nonprofit group that advocates for fair courts, described it as “an extreme approach to an imaginary problem.”

The Illinois Coalition Against Domestic Violence also opposed it, citing concerns about the role coercion can play in crimes like shoplifting and who may be swept up in a broad dragnet.

“If prosecutors understood perhaps how victims were coerced into it, there could hopefully be lesser charges,” they wrote.

At the time, Raoul assured advocates the new law would only apply to “those individuals who were the ‘masterminds’ behind organized crime.”

Governor Pritzker signed the bill into law in May 2022. Since then, the task force has highlighted their arrests on their website.

The task force’s big 2022 bust was Mahdi Alhaw, who was found with $800,000 in stolen merchandise stored in four semi-trailers, some taken from freight trains. Based on court records, Alhaw first came to law enforcement’s attention in August 2020 after he committed a hit and run. Not long after, he was charged with the possession of six stolen vehicles. A year later he was arrested after allegedly threatening to shoot up a night club. A year after that he was nabbed with the stolen merchandise.

Two of the task force’s material cases involved pawn shops. In 2023, police arrested two St. Clair county men who worked at a pawn shop and allegedly purchased and re-sold stolen goods. This year, the task force disrupted an organized retail theft ring run by the owners of Monster Pawn in Sangamon and McLean counties. In total, eight individuals were arrested and charged. In June, they also identified six men allegedly involved in a string of overnight burglaries on area retailers.

The other task force arrests may fit the legal definition of organized retail theft, but don’t appear to be the masterminds behind criminal syndicates. In October 2022, they reported three ORC cases. Four individuals, allegedly masked and armed, were arrested at Gurnee Mills. Three were juveniles. In another case, two women allegedly worked together to steal $3,000 of merchandise from an Apple store at Woodfield Mall. Separately, a man and woman were arrested after allegedly stealing apparel from a Gap store.

The only other reported case involved two women arrested in 2024 for working together to allegedly steal thousands of dollars’ worth of perfume and clothing from several Ulta Beauty and Victoria’s Secret stores. One of them purportedly sold the items through her Instagram account, which landed her an additional charge of managing an organized retail theft enterprise.

The law included one more provision: it created the Organized Retail Crime Enforcement Fund, controlled by the attorney general. Its purpose is to award grants to police and prosecutors throughout the state to “investigate, indict, and prosecute violations of organized retail crime.”

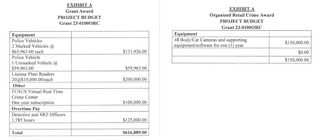

Records obtained via FOIA request show over 120 law enforcement agencies have received some portion of the $15 million given out since the ORC fund was created.

According to our analysis, $5.6 million went toward covering the cost of over 900 ALPRs and their software subscriptions. Eighty one percent of all police departments that received grants spent at least a portion on ALPRs. How many additional ALPRs have been purchased via other funding sources is unknown—we only counted license plate cameras purchased with ORC grant money.

$3.1 million was spent on dedicated real-time crime center software like Fusus. The number of local business surveillance cameras integrated into RTCC’s is staggering. For example, Oak Lawn reported in 2019 that they had 16 business cameras integrated with Fusus. By August 2023, their system had grown to include 898 private cameras, and by June 2024 they were up to 1,073.

A slew of new video surveillance cameras—including cameras that can easily be converted to scan license plates—accounted for another $1.2 million. Over $800,000 went toward forensic tools to break into phones, laptops, vehicles, and other electronic devices—and more than $200,000 was spent on GPS trackers.

Oak Brook Police Department has received more than $1 million from the fund, making them the largest recipient of ORC grants over the past three years. Here’s how the other top spenders measured up:

We have mapped every police department that was awarded a grant. Each point includes the total award by year, along with a summary of how it was spent (where we could determine this with the documents provided):

Other purchases included new vehicles and trailers. Dozens of departments used grant money to pay for officers’ overtime. Several departments noted that they would not have been able to purchase this technology without state assistance. For example, Murphysboro PD received a $126,000 grant in 2023, which is roughly 7% of their annual budget.

Departments used grant money both to pay for Flock ALPRs that were installed pre-ORC funds, and to pay for new devices. Since the creation of the fund, we found the most new license plate readers installed in Wheaton, IL. The crime rate in Wheaton is significantly lower than the national average.

The Chicago Police Department used almost all of their ORC award to pay for overtime.

According to recent records provided by CPD, the department already owns 1,386 ALPRs, including fixed units, vehicle-mounted units, and other mobile units. This represents a significant increase—WBEZ previously reported 433 active ALPRs being used by the department in 2022.

According to progress reports submitted by Illinois police departments from 2024, the technology they bought with state money has, perhaps unsurprisingly, led to many arrests for low-level shoplifting. Very few organized criminal syndicates have been disrupted since the program’s inception. And nearly half of all departments that received grants in 2024 failed to submit a progress report to the attorney general.

Gurnee PD was the only to report an organized crime ring disruption, citing the arrest of 11 individuals and the seizure of two vehicles, $27,000 in stolen merchandise, and $6,000 in cash. Separately, they also arrested one of their own detectives for retail theft.

Gurnee PD’s report also highlighted their arrest of an undocumented immigrant outside Gurnee Mills Mall. He stole nothing, but had a paper bag lined with aluminum foil. He was charged with “unlawful possession of a theft detection shielding device,” a misdemeanor. Court records show he failed to appear for his court case and a warrant was issued. His whereabouts are unknown.

Many progress reports said that they had nothing to report or lacked specifics. Skokie PD reported, “The synergy achieved through this collaborative approach has been instrumental in fortifying our defenses and disrupting criminal networks engaged in illicit activities.”

Morton Grove PD thanked the AG for funding overtime for their officers, noting officers “conducted 80 hours of saturated patrols” which resulted in “no arrests or citations.”

The tiny village of Forest View—population 792—was granted $25,600 for several ALPRs. They reported four thefts for the quarter, one of which involved two men stealing four cases of Modelo beer. They reported zero arrests.

In Schaumburg, police received over $346,000 for a range of tools, including a $6,000 faraday box, digital forensic tools from Magnet and Cellebrite, and mobile cameras. Across two quarters, they reported using these tools in 383 cases—16 (4%) of which were “retail related.”

Some counties have organized their own task forces. Last month, in Cook County, State’s Attorney Eileen O’Neill Burke’s ORC Task Force touted its “first-ever national retail crime blitz” involving more than 100 law enforcement agencies across 28 states. One man arrested in this operation allegedly stole an $8 stain remover. Burke’s office did not respond to our questions about the operation.

Illinois has the second lowest threshold for felony shoplifting in the nation at only $300, which is also now the threshold for organized retail theft. Most states have thresholds between $1,000 and $2,500.

The state’s felony threshold for theft from anyone other than a retailer is $500, making it a more serious crime to steal from people than billion dollar corporations. The ACLU of Illinois found that from 2016 to 2018 alone, more than 5,000 people went to prison in Illinois for low-level thefts that would be categorized as misdemeanors in most other states.

Aaron Gottlieb, an associate professor at University of Chicago Crown Family School of Social Work, Policy, and Practice, spoke with us about our findings. His research focuses on the underlying causes of criminal legal involvement and the implications of policy change.

“All incarcerating people for these kinds of things does is fill prisons and jails,” he said. “It’s not actually going to change behavior or actually reduce the incidents of property crime in any meaningful way.”

Gottlieb believes the decision to allocate these funds and resources to police instead of social programs is a backwards way of approaching public safety.

“It’s pretty well established that the best way to reduce property crime is to make sure people have resources and opportunities, because these are often crimes of survival. Punitive approaches tend to be very ineffective at addressing these kinds of crimes. Investing in things like police or prisons or jails instead of things like social services are very likely to have bad outcomes.”

Ed Yohnka agrees.

“Targeting people who engage in more routine shoplifting with inflated penalties in an effort to get them to implicate others is reminiscent of the tactics of the War on Drugs,” he said. “[Those at] the lowest levels of the distribution chain are overwhelmingly the people who are targeted for enforcement and prosecution. Those tactics largely failed in addressing drug trafficking; there is little evidence that they will work in this instance.”

Encounters with the criminal legal system for any reason can have life-altering consequences. Felony charges are often used to compel the accused to take a plea deal, whether they committed the act or not.

Like six others targeted by police for building the Gaza solidarity encampment on UIUC’s campus, Valentina took a plea deal on the misdemeanor charge offered in order to avoid a felony trial. She then lost her health insurance for several months after the school expelled her, and has been unemployed since October.

“I am legally a criminal. Employers don’t really care how not severe it is. I don’t mean it to sound like woe is me, but it did ruin my life in many ways.”

She also says she hasn’t attended any protests in the aftermath.

“I’ve chosen to step back from protesting until my probation is over…and that’s just what they want. We are entering a new era. There is no safe protest…we don’t really have privacy or rights anymore.”

In response to the misuses of Flock’s ALPR system, Secretary of State Alexi Giannoulias demanded the company block out-of-state police departments who entered reasons for conducting searches that potentially violated Illinois law. He also announced an audit of Illinois law enforcement ALPR usage.

And just last week, U.S. Rep. Raja Krishnamoorthi, the ranking member of the Oversight Subcommittee on Health Care and Financial Services, announced he was opening a Congressional investigation into Flock Safety.

Unlike drones, which have some basic reporting requirements around their usage, ALPRs are not subject to reporting requirements or oversight. Once a law enforcement agency opts to share their network with out-of-state agencies, that data is broadly available to tens of thousands of police officers and federal agents throughout the country.

Flock claims they have blocked the departments who conducted ALPR searches related to immigration enforcement. They also say they rolled out an update that will automatically block searches based on keywords, like “abortion,” or “immigration,” though officers can still enter anything they want.

Asked about the effectiveness of keyword blocking, a Flock spokesperson acknowledged that it’s not a “silver bullet,” and requires active oversight.

“Preventing unlawful searches requires a layered approach by all parties—combining technology, transparent audit trails, and strict policy enforcement by both law enforcement and our elected officials—to make sure protections are both real and enforceable.”

As Unraveled previously reported, police departments also don’t always know who is accessing their own systems. In what could be a violation of state and federal law, a police officer in Palos Heights was caught sharing his Flock database password with DEA agents. One used it to look up license plates potentially belonging to immigrants.

Just this past weekend, Denver announced they would stop sharing ALPR data with Loveland, Colorado when local media revealed they had been sharing information with Customs and Border Patrol.

In the face of all of these flaws, Yohnka has called for all communities to “immediately institute a pause in implementing new surveillance technology” at least until they can “adopt detailed, publicly-transparent policies that protect privacy.”

Some communities are doing just that. In Austin, Texas, the city council voted in June to cancel their contract with Flock Safety. Austin had one of the most restrictive ALPR policies in the nation, and still found it insufficient to ensure privacy protections.

A federal judge recently ruled that a lawsuit filed by the Institute for Justice against Norfolk, Virginia can proceed. The suit alleges the town’s dragnet of more than 170 ALPRs constitutes a Fourth Amendment violation. A similar lawsuit filed in Illinois by the Liberty Justice Center was dismissed by a federal judge in April.

Last week, the Institute for Justice also launched The Plate Privacy Project, with a mission to “propose model legislation in state legislatures to protect against warrantless ALPR surveillance, partner with local grassroots activists to help them resist the use of these cameras in their communities,” and to litigate where necessary.

For years, activists in Oak Park, a suburb on Chicago’s western border, have pushed back against ALPRs. They’ve documented racial disparities in Flock initiated stops and errors that led to unnecessary police interactions. This month they achieved a victory when the Oak Park board of trustees voted to cancel their current Flock contract. Community members and trustees cited concerns about privacy, effectiveness, and a lack of trust with the vendor in safeguarding their data.

Trustee Brian Straw raised concerns about Flock’s lack of meaningful safeguards to ensure compliance with Illinois law.

“The only reason we know that our data was searched by ICE is because somebody…was dumb enough to put ‘immigration enforcement’ as the purpose for their search,” he said. “If they had instead put anything else in there, we never would have known.”

Federal violence and persecution against the immigrant community has already come to Illinois, as ICE snatches migrants from immigration courts and vehicles, while also assaulting protesters. ICE has already equipped agents with mobile facial recognition tools.

John Slocum, executive director of Refugee Council USA and long-time Oak Park resident, eloquently summarized what is as stake:

“At a time when the federal government is making overreaching attacks on norms, institutions, civil rights, due process and the rule of law, Oak Park should not be spending taxpayer funds on a technology that can easily be abused to advance a universal system of authoritarian style surveillance and control.”

Chibuike Enyia, another trustee who voted to end the contract, said he worried about migrants, people seeking reproductive healthcare, and transgender community members.

“They don’t know when that camera is going to be turned on them,” Enyia said. “And when some form of persecution comes to their doorsteps, I don’t want to be the one that aided in that.”

The Organized Retail Crime Grant Fund received another $5 million for the upcoming year and is currently soliciting applications from police departments.

Unraveled has verified a hate speech-laden X account belonging to U.S. Border Patrol agent Timothy Donahue, who was seen in numerous viral videos during Operation Midway Blitz. He and another agent, Thomas Parsons, have now been identified via public records released by the City of Evanston.

Ex-Waukegan cop, convicted of felony misconduct for 2019 beating, gets jail time on delay.

Lake County judge returns mixed ruling in the first of two criminal trials against ex-police officer Dante Salinas.